Archetypes in Religion and Beyond

A Practical Theory of Human Integration and Inspiration

Now published, available from Equinox and major online booksellers

“Robert M. Ellis has put together a magisterial work on the archetype, bringing together empirical, philosophical, comparative religious and Jungian approaches into one carefully worked out theory. A rich, deeply thought provoking and remarkable synthesis.”

Erik D Goodwyn MD, Associate Professor and Director of Psychotherapy Training, University of Louisville; author of ‘The Neurobiology of the Gods’.

The term ‘archetype’ as used by Jung is of huge value because it enables us to understand the relationships between different types of symbol that humans invest meaning and value in. These include the hero, the shadow (e.g. Satan), the feminine (anima) or masculine (animus) and God. Crucially, the idea of archetypes allows us to distinguish between the helpful experiential meaning of these archetypes and their projected form, when we deludedly locate our own potential in someone else.

Archetypes have become a popular idea, but the way that they are understood often does not help us to see their value in practice. Even Jung’s own account of them contains contradictions and unnecessary speculations. This book puts forward a new theory of archetypes that is substantially adapted from Jung’s, for instance letting go of the unnecessary hypothesis of the ‘collective unconscious’. It simplifies the categorization of archetypes into four basic functions, and shows how those functions can helpfully be used to help us maintain inspiration and value over time, addressing long-term human needs in a range of changing conditions. Whilst the positive value of archetypes is to help us fulfil these functions, they can also be readily diverted from doing so through projection. Projection leads us into rigid beliefs that supplant the meaning and inspiration we should be getting from the archetypes.

This thesis about the functional role of archetypes becomes the basis for a critical account of religion as capable both of practical and dogmatic forms, that can be readily illustrated through their use of the archetypes. This is illustrated in relation to a range of examples from different religious traditions, and is also applied to ‘secular’ concepts that are often seen as lying beyond religion, such as nature, truth or rationality. It also provides the basis for a moral philosophy in which integrated rather than projected uses of the archetypes can be used as a basis of judgement in a wide range of issues affecting our lives. This approach is further supported through exploration of its links with the operation of reinforcing or adaptive feedback loops in systems theory, with Iain McGilchrist’s arguments on the over-dominance of the left brain hemisphere, and with the role of bias in cognitive psychology. Suggestions are also made for empirical research that could potentially give further support for this theoretical approach.

This book thus provides a synthetic argument that is intended to bring together potentially valuable ways of thinking about archetypes from different disciplines and show their relationship – crucially, also, for a practical end. This argument is in some ways a development of my previous work in other books on Middle Way Philosophy, but in other ways provides an alternative route into some of the same points that can stand independently. It is a critique and development of Jung, but goes a long way into territory that may also be unfamiliar to most Jungians. It offers a functional theory of religion, but one whose implications go well beyond what is conventionally seen as ‘religion’, and involves breaking down many unhelpful distinctions between ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ territory. If the extent of the synthesis seems complex, the central idea of inspiration can provide a relatively simple summation of the meaning of the book: that inspiration over time is the crucial human function of religion, and that the recognition of this point may have far-reaching consequences.

Read the Introduction to this book

Summary by chapter

Introduction

This a practically-led approach to archetypes and how they function to inspire us, rather than what they ultimately are. Archetypes need to be distinguished from symbols, and are understood here as diachronic schematic functions: that is, a way that symbols are continually meaningful and inspiring to us over time.

1. What is an Archetype?

a. The Experience of Archetypes

Symbols are meaningful to us through the associations made by our bodies, and archetypal symbols particularly help us to fulfil long-term embodied needs. These needs may be to achieve goals, avoid threats, form relationships with others, and fulfil wider potential; but they are not always fulfilled if the association becomes rigidified.

b. The Universality of Archetypes

Universality in a theory of archetypes is an aspiration for consistency (with a moral value) rather than an absolute claim about ubiquity. The basic archetypal functions (not specific symbols) seem likely to be universal because they are based on features of general human physiological need.

c. Archetypes as Embodied Schemas

Archetypes are embodied schemas in terms of the theory of Lakoff and Johnson – that is, sets of associations between symbols and experiences. These associations help us recall and reinforce different forms of inspiration when we need them, and so develop the openness and reflectiveness accompanying the symbols.

d. Archetypes as Metaphors

Archetypal symbols are metaphorical developments from embodied schemas, through further and increasingly complex association. Just as metaphors die when they become literalized, reduced to a supposedly represented world, archetypal symbols become dead when they are projected as part of the represented world, rather than of our experience.

e. The Baggage of the ‘Collective Unconscious’

‘Unconscious’ in Jung’s account of archetypes is an unsatisfactory term because it entrenches a dichotomy (against the ‘conscious’) for a quality we experience incrementally, and ‘collective’ also unnecessarily dichotomizes ‘personal’ experience from genetically shared experience. Diachronic schematic function fulfils the same need to define archetypes, without Jung’s speculative assumptions.

f. The Baggage of Platonism

The Jungian idea that archetypes are Platonic forms or essences effectively undermines the helpful operation of archetypal function by making us think representationally instead. The search for essences has a helpful critical role in Plato’s dialogues in helping people realize their lack of knowledge of them, but doesn’t justify definite essentialist assumptions.

g. Archetypes and Religion

Jung’s ideas about religion can be helpfully clarified as suggesting that religion can help us integrate the archetypes – provided they are not kept in conflict through projection. There is thus a distinction between practical religion that fulfils this need, and dogmatic religion that instead hijacks that function to maintain projected beliefs as the supposed ‘truths’ of religion.

h. Archetypes, tradition and modernity

The differences between traditional and modern societies seem to broadly depend, not on using or not using archetypes, but on the aspects of their function that we fulfil. Traditional societies maintain the diachronic function of archetypes but not the schematic, whereas modern societies maintain the schematic but not the diachronic.

i. Evidence and Testability

In principle, the operation of schematic functions can be evidenced by testing their operation amongst a wide range of people – this could take the form of a development of previous research into prototypes. Diachronic schematic function could specifically be tested through lifetime studies of maturation (such as those discussed by Vaillant), particularly using the psychological measures of wisdom developed by Grossmann.

2. The Projection of Archetypes

a. The Projection Process

Projection is an aspect of absolutization: it occurs when one feature of a symbolic object is taken to be ‘essential’ and the only relevant feature. The Jungian understanding of projection as merely bringing subjective features into an object is unhelpful because it does not differentiate projection from provisional belief.

b. Reactive Projection

Reactive projection is a polarized over-reaction to projection that creates further projection, when it is assumed that a projected feature must be false. However, we can be no more certain of the absence of a feature from it being projected than we can its presence.

c. Projection as Metaphysical Belief

Projection is equivalent to metaphysical belief, because all such beliefs involve claims about ‘essential’ or ‘real’ features (or their absence). Different types of metaphysical belief can be associated with the projection of different archetypal functions – for instance, the projection of God’s ‘existence’ from the transcendence function.

d. Projection as the denial of embodiment

Projection assumes a view of meaning that denies embodiment by assuming an entirely abstract representation, where meaning lies in objects rather than in experience. As we become concerned with representational ‘truths’, we simultaneously lose awareness of the range of sources of meaning in our bodies.

e. Projection as left hemisphere over-dominance

The over-dominance of the left pre-frontal cortex provides an understanding of the basis of projection, as it involves the dominance of representations. Diachronic archetypal meaning is difficult to access under this over-dominance, given the left hemisphere’s inability to experience time passing, so it gets reduced to projections that ‘exist’ or ‘don’t exist’.

e. Projection as bias

Biases are established shortcuts that cease to help us in changing conditions, all involving confirmation and repression of cognitive dissonance. Believing a biased view to be true (or over-reacting to it as false) is also a projective process, and different biases can be identified with different types of archetypal projection.

f. Projection as reinforcing feedback

In systems terms, projection takes the form of reinforcing feedback loops that multiply their own effects and disrupt the wider system. These projections in turn can be seen as disrupting the balancing, adaptive feedback involved in archetypal functions.

g. Projection as power

Projected beliefs are tools of power, because they are impossible to question within the terms of the absolute framing adopted. Group biases reinforce the absolute authority of this framing, so that archetypal projection in religion and beyond is constantly reinforced by group power.

h. Projection as evil

The concept of evil can helpfully refine our capacity to identify threats, especially those that are long-term and human in origin. We intuitively recognize the features of projection and absolutization as evil in our recognition of ‘evil’ traits that are strongly left hemisphere traits – such as cruelty, obsession or instrumentality.

3. The Integration of Archetypes

a. The Middle Way and the Integration Process

Integration reduces projection, not by reaching ‘reality’, but by dialectically reducing the social and psychological conflict that results from projective repression of alternatives. Conflicts are resolved by reframing the assumptions that create them – an integrative process that applies the Middle Way, avoiding opposing absolutes with scepticism, provisionality, incrementality and agnosticism.

b. Integration and mindfulness

Mindfulness practice integrates by contextualizing conflicting beliefs in embodied experience. Neurally, it stimulates the hippocampus, task positive network, and greater inter-hemispheric connectivity, which all help to boost contextual experience and maintain awareness over time.

c. Integration and the Arts

Integration is also enabled in the longer term by making new neural connections of a kind that help us understand new symbols. Compassion is an integration of meaning in relation to others, and the creation and appreciation of the arts is a key practice in creating new resources for archetypal functions, whilst avoiding their projection.

d. Critical universalism

The most direct way to integrate conflicting beliefs is through critical awareness of their limitations. This can be cultivated through the skills of critical thinking, together with the aspiration to universality that gives critical awareness a wider (‘emotional’ as well as ‘rational’) context.

e. Working with Traditions

Traditions are complex systems that pass on group-identity over time and develop their own adaptivity – they are neither monolithic nor infallible. To support the archetypal functions embedded in traditions, individuals need to learn to ‘work with’ traditions provisionally, rather than projecting absolute authority onto them.

4. Categorisation of Archetypes

a. The Basis of Archetypal Categorisation

The four functional archetypes can be understood in relation to three functional axes: attraction/ repulsion, self/ other and projection/ integration. Different combinations of these create the hero, anima/animus, shadow and God functions.

b. Variations of the Four Archetypes

Archetypal functions are often confused with specific symbols, but very different symbols can fulfil the same function. A given functional archetype can thus vary according to the types of symbol that are used to fulfil it, and also according the brain events that may fulfil that function.

c. The Hero and the Ego

Our ego leads us all to have goals, but to adapt we need to maintain, modify, or even transform those goals over time. The hero function inspires us through many symbolic forms, even to the extent of heroically trying to sacrifice the ego itself.

d. The Anima/ Animus, Sex and Specialization

The function of the anima/animus is not to reinforce essentialized ideas about gender, but to be inspired by the attractive other, whatever form this takes. This can help compensate for any type of over-specialization, and help us form relationships to engage with new perspectives.

e. The Shadow, Death and Suffering

We may immediately focus on death and suffering as the shadow because they are threats, but the function of the shadow archetype is instead to help us differentiate genuine threats over time and to focus on what we can change rather than trying to change all conditions.

f. God and Religious Experience

The archetypal God function arises from the integration of the other three functions, and inspires through association with the open potential of what is often called religious experience. It can be symbolized in a wide variety of ways, some impersonal and largely conceptual (Nature, or Truth), but is overwhelmingly vulnerable to constant projection.

g. The Middle Way Archetype

The Middle Way may be regarded as a further archetypal function: that is, as an inspiration to remind us of the method for fulfilling open potential in relation to the current conditions. Symbols involving ambiguity, marginality and balance may fulfil this combinatory function.

5. Archetypes in Religious Traditions

a. Ethnic and Universal Religion

The universality of a religion is not necessarily schematic, but can instead be dogmatically fixed on certain concepts and beliefs. Ethnic religions may be exclusive, but also less rigid in their use of archetypal symbols.

b. The Buddha

The Buddha can fulfil the God function for us regardless of his formal status, but more distinctively offers the clearest symbol of the Middle Way function in the story of his early life. However, this can also easily be projected, like any other archetypal symbol.

c. Mahayana Symbology

Mahayana Buddhism offers a rich symbolic development of all the archetypal functions, in forms that are both personal (e.g. bodhisattvas) and impersonal (e.g. mandalas). It also has a tradition of provisionality in the use of symbols, though this can be undermined by the unconditional use of authority.

c. Hinduism: The Great Appropriation

In Hinduism the use of archetypal symbols for personal integration is developed in a wide variety of ways in relation to all the functions. However, it is also appropriated for socio-political ends to support the caste system.

d. The Archetype of Nature in China

Archetypal symbols in China often emphasise natural order, which can fulfil the God archetype by inspiring integration in a wider system, or alternatively be projected. Hero and anima figures are also well developed, but the development of shadow symbols is more debatable.

e. Yahweh, Idolatry and Literacy

The archetypal insight of the Hebrew Bible is its emphasis on God as schematic rather than as a specific symbol, expressed in the forbidding of idolatry. This tries to avoid projection for pre-literate people, but Judeo-Christian tradition has often missed the bigger issue of the idolatry of concepts by the literate.

f. Graeco-Roman Tradition

Graeco-Roman mythology is much stronger on the symbolization of hero, anima/animus, and shadow functions that on the God archetype. This is a gap that was initially addressed conceptually for an elite by Greek philosophy, and then more fully by Christianity.

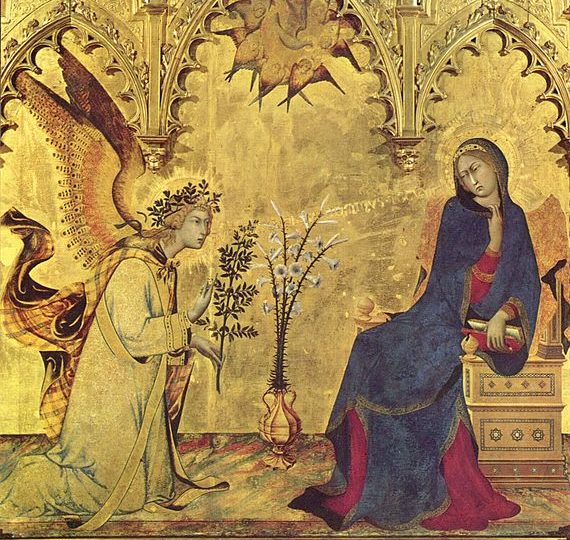

g. Christ

Christ (as distinct from the historical Jesus) symbolizes a new emphasis on the universality of the God archetype, but also evokes the Middle Way archetype through the ambiguity of divine and human. The crucifixion and resurrection can symbolize the emotional power of a shift from reinforcing to balancing feedback.

h. Christian Mythology

Christian heroes (saints and prophets), Mary and Satan can all help Christians to develop the other functional archetypes into the God archetype. However, all of these functions are also undermined by literalism: for instance through martyrdom, sexual repression and fear of hell.

i. Christian Mysticism

The Christian mystics, by prioritizing experience over dogma, have contributed much through the ages to maintaining the God function free of projection. They have also developed connections between the God archetype and other archetypes.

j. Islam: The Tawhid

The Islamic doctrine of tawhid emphasises the universality of the God archetype, and reinforces this through disciplined practice and the avoidance of idolatry. However, this seems to have been undermined by a heavy reliance on repressive rather than integrative approaches.

k. Islam: Jihad and the Satanic Verses

The doctrine of jihad evokes heroic archetypes, but is usually repressive, even when focused internally. Despite some more integrative approaches to the shadow, the Satanic Verses episode also illustrates a highly repressive approach to the anima in Islamic tradition.

l. The Kabbalah

The kabbalah has managed to integrate different archetypal functions in a rich and systematic symbology, particularly illustrated by the sefirot or ‘tree of life’. This incorporates an embodied approach to the God function that tries to avoid its projection, and balances the contribution of a range of human qualities.

6. Archetypal Function in ‘Secular’ Concepts

a. Nature

‘Nature’ is a highly manipulable concept that can inspire us through the God, anima or shadow functions, but just as easily be used to claim a dogmatic totality. It draws our attention to wider systems, particular beneficial environments, and aesthetic experience, but is also projected both scientifically and morally.

b. Goodness

‘The Good’ is helpfully seen archetypally rather than metaphysically. Each of the positive archetypal functions correlates with an approach to ethics (deontological, consequential, or virtue): these archetypes inspire moral judgement, and the overall good is their integration.

c. Truth

The concept of truth inspires us archetypally towards justification, trustworthiness and consistency, but this is constantly undermined by projective claims to possess propositional truth. Archetypal truth can thus help us avoid the projections of both absolutized and relativized truth.

d. Beauty

Experiences of beauty can be a constant source of inspiration either aesthetically or symbolically. This often serves the anima/animus function, but can also develop into the God function, as long as it is not projected into a mere concept of beauty to be possessed.

e. Rationality

Rationality, reason and logic, understood as archetypal concepts, inspire us towards increasing consistency of belief linked to embodied confidence. However, these concepts are constantly projected in the rationalist assumption that logical models applied to propositions somehow enable us to represent the world.

f. Humanity

The assumption that an ideal of ‘humanity’ is opposed to God is strange given that it has very similar archetypal functions. To avoid it being merely a reactive projection, humanism needs to be interpreted agnostically.

g. Democracy

Democracy in modern discourse is often used in an archetypal way rather than just meaning a system of government. It evokes the potential for human solidarity, reflection, and consent, and thus integration at a socio-political level: which can inspire us helpfully as long as it is not projected into a populist shortcut.

h. Health

The concept of health is often an archetypal symbol for the God function, closely linked to our embodied experience of integration overcoming bodily conflicts. The archetypal function becomes projected when health is a mere concept, often inspiring obsessive behaviour with limited contextual awareness.

Conclusion

The arguments of this book stand or fall on their practical application, rather than as interpretations of Jung or any other source, and link into further arguments about the Middle Way elsewhere. They have rich implications, not just for practice, but also for the prompting of further research in a wide variety of disciplines that could help to develop our practical understanding of the operation of archetypes.